Naomi Adamu is quiet. As she talks she rarely makes eye contact, keeping her voice low and steady.

Upon meeting her, few would suspect she survived one of the most harrowing experiences a young woman could go through. But her timid demeanour belies an extraordinary strength of character.

Naomi, 24 at the time of the attack, was the oldest of more than 270 students from the Chibok Government Secondary School for Girls abducted by the Islamist militant group Boko Haram in April 2014.

Her classmates referred to her as Maman Mu, Our Mother. Her education had been interrupted by health problems as a child.

She is now the main protagonist in a new book on the so-called “Chibok girls”.

The book explores the girls’ time in captivity in detail, and shows how the social media campaign that made them famous also made it harder to secure their release. Their fame had made them precious commodities, too valuable to let go.

During the three years she spent with Boko Haram, Naomi refused to bow down to pressure to marry one of their fighters, or convert to Islam.

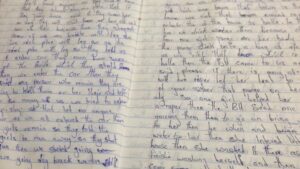

Instead she and another classmate wrote secret diaries in textbooks they were given to write Islamic verses. She kept them hidden in a makeshift pouch tied to her leg.

“We decided that we should write down our stories,” she tells me, “so that if one of us got to escape, we could let people know what happened to us”.

She shows me one of the diaries, a lined text book with a fraying cover. In it is a letter to her dad, written just before Christmas of the year they were kidnapped.

“Dear my lovely dad, I miss you so much in this moment.

“Dad, I want to see you, I’m so worried about you and mum and the rest of the people at home.

“I wasn’t aware that this could happen to me, none of us who Boko Haram kidnapped realised that. By the Grace of God dad, I miss you so much.

“I want you to help me in prayer all the time so that I will defeat the devil each time he comes to torment me. So dad, I will like to stop here.

“I miss you so much. Goodbye have a nice day.

Besides being separated from their loved ones and not knowing how they were doing or if they were even alive, the girls suffered many hardships.

They were moved frequently to avoid detection by the myriad armed forces looking for them, including the Nigerian military, foreign mercenaries and American drones.

Apart from a brief period in the town of Gwoza, captured by Boko Haram in late 2014, they spent most of their time in camps in the Sambisa forest, the group’s main hiding place.

“It was a very difficult time for us in Sambisa,” Naomi explains, “there was no food, no water. We even had to use soil to clean ourselves up when we were on our periods.”

Senior Boko Haram militants were constantly trying to get Naomi to marry one of their fighters. They believed seeing her get married would help convince the younger girls to follow her lead.

Every time she refused she would be beaten brutally and threatened with death.

When I ask how she knew she would not be killed for refusing to obey her captors, Naomi says she was not ready to get married.

Her insubordination led her and others to be introduced to the leader of Boko Haram, Abubakar Shekau. But during the meeting he made a surprising revelation.

“Shekau told us that he didn’t abduct us to marry us off, but because he wanted to put pressure on the government to release his men who were in detention.”

The discovery strengthened her resolve and soon there were other rebellions.

When the militants kept her and some of the more stubborn students apart from their peers, depriving the weaker girls of food in order to force them to marry, Naomi and her friends smuggled food to them.

They sang hymns in front of their guards, quietly at first, then more boldly. Most of the kidnapped students were Christians. They wrote down their favourite Bible verses and prayers in their diaries.

At the time she thought Boko Haram was on its last legs.

“I didn’t think Boko Haram would still be active today because when we left there, they were splitting into two groups, so we thought they were over. Some of them were in Sambisa, whilst some were Kangaroua.”

But the social media campaign to free the girls, led by celebrities including the US first lady at the time, Michelle Obama, had propelled them to fame and shown Boko Haram how valuable school children were as captives.

– Culled from BBC News

SocietyGazette.com Society Gazette News

SocietyGazette.com Society Gazette News